Creativity is in the eye of the beholder.

What does creativity even mean?

A Google image search for the term “creative” results in a browser window flooded with brightly colored images. The most common representation is a depiction of the brain’s two hemispheres: one side with data and charts flowing out, and the other bursting with colorful swirls. The unifying theme in all these images is the vibrant use of color.

To create is to make. The suffix -ive (derived from the Latin -ivus) means “that which performs or tends toward a particular action.”

So, when combined, creative describes an individual who tends to create. But isn’t that true of all humans? So how did creativity become a unique and coveted ability attributed to only a select few, with the rest needing to be taught how to tap into it?

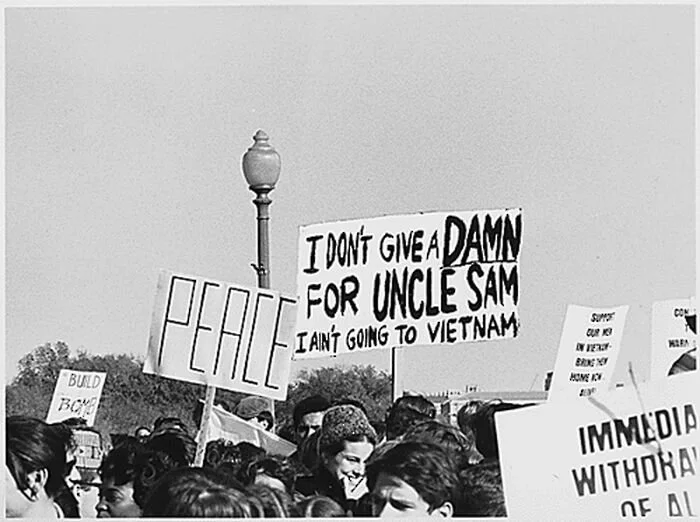

Image: Flickr

The post-war counterculture movement in America sparked the spirit of self-expression, exploration, and rebelliousness. There was a desire to break away from conformity, which was viewed as anti-democratic and akin to communism and mass society. This anti-conformist and out-of-the-box thinking—initially associated with artists—began to permeate science, technology, and consumer culture as people craved something new.

We continue to fuel this hunger for novelty, perpetuating the behaviors inherent in the current capitalist system.

Image: Flickr

Joy Paul Guilford's curiosity about "creative behavior," highlighted during his tenure as President of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1950, gave rise to the creative research movement. At that time, the field of psychology was dominated by behaviorism, which had been the primary focus of study since the 1920s.

Behaviorism, with its mechanical approach of strictly observing rats, came under criticism for reducing human beings to mere animals. We are mammals.

Behaviorists argued that human behavior could be controlled and shaped, potentially leading to collective harmony. However, this understanding of human behavior's malleability was later criticized for being misused in mass persuasion techniques—most notably during the Holocaust and against American prisoners in Korea.

Guilford’s desire to define and quantify creative behavior was, in itself, a creative act. By thinking differently and going against the status quo of behaviorism, he was feeding his own curiosity and challenging the dominant approach of his time.

Although creative researchers, driven by curiosity, aimed to study and understand creativity as a rebuke to behaviorism, their research had significant limitations. While they succeeded in distinguishing creativity from intelligence, genius, and divergent thinking, their subjects were predominantly white men from highly educated and eminent backgrounds. As a result, creativity was defined by the communities in which the research was conducted, making it simultaneously universal and rare—accessible only to highly educated individuals in specific professions.

Moreover, researchers restricted their focus to productive labor in the workplace, assuming that creativity only mattered in professional settings.

This segregation of individuals into distinct groups creates a divide, pitting people against each other, much like divisions based on race, religion, and caste. It is important to note that these studies were conducted on educated people in a Western context. Therefore, they measure only American definitions of intelligence, creativity, and genius—not the full spectrum of human potential across different cultures and backgrounds.